Agogo Mission Week 2022: A Medical Student’s Experiences

ABOUT ME

Hi! My name is Ryian Owusu and I am a second year medical student at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine. Ghana Medical Relief allowed me to do two things that mean the world to me: practice medicine and learn about my family’s heritage – and for that I thank GMR and everyone who makes the mission possible.

Being a medical student, there is so much to learn in such a limited time. Some describe it as drinking water from a firehose – an overwhelming amount of information that must be understood and applied to clinical practice. My desire to write this blog was to be able to share my experiences and remember the patients, students, physicians, nurses, PAs, and volunteers that I met and interacted with. I want to remember the gratitude that the villagers of Agogo had for GMR and extend my own appreciation to them for allowing us to come serve and me (as a medical student) learn more about clinical presentations that will help prepare me to treat my future patients.

During our week in Agogo, we provided free healthcare services to 6,468 people. There were 15 eye surgeries, 18 major surgeries, and 120 CPR participants. I wish I could detail all of the different diagnoses I saw and all of the lives we impacted, but there’s just not enough hours in the day (or website space). I have described in detail one to two cases I saw from each of the clinics I worked at throughout the week: family medicine, OBGYN, surgery, pediatrics, ophthalmology, and urology. I hope you enjoy experiencing the mission through my eyes and choose to join us on our next one.

7/25: Family Medicine

First day of clinic! I am so excited to be back in Ghana, doing what I love with so many amazing people around me. I am starting the week off at the family medicine station, where we already have each seat of the waiting area occupied by a patient. The doctor and I look at each other with a huge smile on our face as she says “you ready?”. I give her a quick nod and we turn to face our first patient of the day.

Our first patient, a middle-aged female, sits across from us and hands the doctor her triage note. The patient has a large, uniform mass on the front of her neck, indicative of a goiter. Goiter can be caused by a multitude of things such as iodine deficiency, grave’s disease, thyroiditis, pregnancy, etc. The patient explains that the mass has been present for a while and she feels as though it is enlarging. It causes her more discomfort than pain symptoms, but it has been bothering her enough that she wants to know her options for treatment.

I assist the doctor in performing a physical exam, by first palpating the thyroid gland. I gently run my fingers over the entire surface of the gland and I am not able to feel any isolated nodules, but instead a diffusely enlarged gland. I ask the patient if she feels any pain during my palpation and she shakes her head signally no. In order to ensure the mass is her thyroid, we ask the

patient to take a sip of water. She raises the water bottle up to her mouth and I watch the mass move swiftly upward as the patient swallows. She experienced no pain during the maneuver but did show some difficulty. With the trachea and esophagus in close proximity, the enlarged thyroid gland can cause compression of the esophagus – leading to difficulty in swallowing, as seen in this patient. The doctor explains the findings of the physical exam, along with different treatment options. With the compression of nearby structures and the size of the gland, surgery would be the best course of action. The patient nods showing that she understands and the doctor begins scribbling notes on the patient’s triage paper. She finishes the note with her signature and sends the patient on her way.

7/26: OBGYN

A 29-week pregnant woman enters the examination room with the OBGYN, OB nurse, and second year medical student. I can tell on her face that she is anxious about what she’s going to explain next. She details that this is her second pregnancy and she has not received prenatal care. She has recently been having symptoms of painless vaginal bleeding and is concerned about the health of her baby. At this level of my education, my first thought is that the mother could be having a miscarriage, due to this diagnosis being a common cause of vaginal bleeding during pregnancy. The doctor looks cool, calm, and collected. He has seen this before many times. He comforts the mother and tells her that he will perform a pelvic exam followed by ultrasound to check the status of the fetus.

The doctor calls me over to assist him with the exam. The nurse prepares the station, placing a sterile speculum, glob of lubrication, flashlight and gloves on the side table. The doctor grabs the speculum, as I grab the flashlight, and he counts 1,2,3 then inserts the speculum into the vaginal canal. The doctor locates the cervix and we see bright red blood protruding from the external os. He gently removes the speculum and rises to stand on the side of the supine patient. “Grab the tape measure”, he asks from me. As I return, the doctor has one hand placed at the top of the patient’s pubic bone and the other on the fundus of the uterus. He asked me to measure the distance between the two points to determine the fundal height – which corresponded to a 29 week pregnancy.

He pulls over the ultrasound machine and spreads gel over the transducer. He warns the patient of the cold feeling she is about to feel and places the transducer near the crease of her pregnant stomach. At the bottom of the uterus, he notes the presence of the placenta partially covering the opening to the cervix, a condition called placenta previa. This condition classically presents in second trimester mothers with painless vaginal bleeding. The doctor hands me the transducer and asks me to locate the anatomical structures of the growing fetus. I find the baby’s head, followed by the back, all the way to the toes. I place the transducer over the baby’s back and can see the heart beating on the ultrasound like the sound of a drum – bump bump, bump bump, bump bump. The doctor reassures the mother that her baby is stable and a rush of relief spreads across the mom’s face. He explains to her the next steps that should be taken to ensure a healthy pregnancy and delivery. With the ending of their conversation, the mother rises from her chair and walks out the door.

7/27: Surgery

Hydrocele

I present to the hospital, bright and early, in the village of Agogo. I change into the hospital scrubs, grab a hair net, and appropriate mask. The attending introduces himself and escorts me and another volunteer towards the OR to scrub in with him, the nurse and resident. He demonstrates the correct technique and hands me the scrub brush layered with soap to clean in between my fingers, under my nails, and up my arm. I watch as the water rinses away the soap bubbles and I repeat. Once finished, we walk into the OR where the nurse assists in the gowning and gloving of the attending and I. I become overwhelmed with excitement to observe all of the cases on schedule for the day. The first patient arrives through the door and is transferred from the gurney to the surgical bed. The patient has an enlarged left-sided scrotum that appears to be filled with fluid. The skin is extensively stretched and measures to the size of a softball. The surgeon, residents, and students gather around the patient and begin prepping the area for surgical repair. The resident gathers the tube and bowl in preparation for drainage of the hydrocele. The surgeon makes a slight incision into the skin of the patient’s scrotum and places a tube with one end inserted into the tunica vaginalis and the other hovering into the bowl. The top of the draining tube is released and “whoosh” a gush of fluid leaks out from the scrotum and into the metal bowl. The fluid continues to rush out and fills the bowl to the very top. Once the fluid is completely drained, the resident steps in to suture the area. The patient is sent to the nurse’s station for continued monitoring and is released by the end of the day.

C-section

A soon-to-be mother rushes into the emergency OR within the hospital. The mother’s pregnancy was complicated by third trimester placental abruption, where the placenta detaches from the uterus, which requires an emergency cesarean section. The anesthesiologist administers medication to prepare the patient for surgery. The obstetrician and gynecologist takes his place at the side of the patient and cleans the abdomen in preparation for incision. He creates a long horizontal incision at the top of the mons pubis. The layers of the abdomen become visible one by one– skin, fat, fascia, muscle, and peritoneum, until the uterus is identified. Another incision is made into the muscular organ and a slight poke into the amniotic cavity. The doctor reaches his hands into the uterus and pulls out the baby – releasing him from his mother’s womb. The baby, lifted in the air now, appears a blue-gray color and a few seconds go by of complete stillness. The baby then lets out a roaring cry as the color red/pink begins to take over his complexion. The umbilical cord is cut and the baby is sent over to a nearby examination table for the pediatrician to determine the Apgar score. The doctor reaches into the mother’s uterus once again to completely remove the partially detached placenta and places it onto the table next to the patient. The pediatrician brings the newborn baby over to see his mother for the first time. The gift of life, right before my eyes. The mom reaches for her baby, placing him on her chest, as she continues to be stitched up and later sent to recovery.

7/28: Pediatrics & CPR

Pediatrics

A 7-year-old boy slumped in her mother’s lap presents to the pediatrician and I. The boy looks miserable and his mother explains that he has been feeling extremely ill for the past couple days. The patient vitals, taken at triage, were significant for a 101-degree fever and pulse of 100 bpm. After taking the patient’s history, the doctor, boy, mother, and I enter the examination room. While examining the patient, we note the color of his eyes has changed from an egg white to a pale yellow. The eye lids on the emotionless boy’s face are puffy and tender to the touch. I lift the patient’s shirt, to expose his belly, and proceed to perform an abdominal exam. On inspection, there is a large bulge within the patient’s abdominal cavity. I lightly apply pressure to the left side of the abdomen and during palpation I am able to feel a large portion of the spleen, an organ that is not typically able to be palpated.

I grab my stethoscope and place the diaphragm upon the patient’s chest. Whoosh-thud, whoosh-thud, whoosh-thud fills my ears as I auscultate the patient’s chest – diagnostic of a holosystolic murmur. The pediatrician looks at me and says “we need to refer this family immediately to the hospital. This boy is very ill and requires medical treatment within the hospital”. The doctor does not mention a specific diagnosis, as this patient requires additional labs and imaging modalities. Upon our return to the station, the physician writes a referral note followed by a scribble of his signature and hands me the note to add my signature as well. He explained to the mother the findings on the physical exam and emphasizes that the boy requires immediate attention at a separate facility. Following the conversation, the concerned mother grabbed her child, the note and hurried to the hospital.

CPR

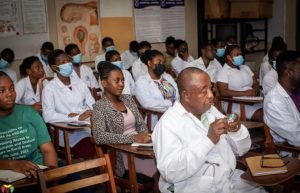

A group of volunteers from the GMR team walk along the unpaved road towards the nearby classroom. When we arrive, there are empty tables at the front, where we drop our bags filled with CPR equipment. The team and I remove the adult and pediatric dummies and place them in alternating fashion on the tables. A class of PA and nursing students trickle into the classroom and find their designated seats.

We run through introductions and explain to the class our purpose for being there. The GMR nurse on our team verbally explained the steps of CPR in extensive detail for both an adult and pediatric patient. Following verbal instruction, the rest of the team and I, physically demonstrated the proper technique on the dummy in front of us. I began to give 30 compressions, ensuring there were two green lights, followed by two breaths. After all demonstrations, the students (2 per dummy) made their way to the front of the class to practice how to give appropriate CPR.

7/29: Ophthalmology & Urology

Ophthalmology

Back in the OR I stand, dressed in scrubs and a hairnet ready to witness the procedure of cataract removal. The patient waits at the nurse’s station for his local anesthesia to kick in. As the nurses are bringing the patient into the OR, the doctor explains to us that cataracts are extremely prevalent within the community and is the leading cause of blindness within the village of Agogo. Therefore, this procedure is highly desired and performed frequently in the realm of ophthalmology. He emphasizes that the entire procedure lasts about 15 minutes—15 minutes for a patient who entered the OR blind to leave with their eyesight again.

The doctor assumes his position and gathers the necessary tools, with his surgical technician next to him. On the other side, is a large device with the capability to see the procedure closely, that is used for teaching purposes. I peer through the eyepiece so that I am able to see exactly what the doctor is seeing. The doctor uses his scalpel to create a small incision at the top of the patient’s eye and slowly makes his way to the opacified lens. There are several times where the eye is rinsed and the doctor goes back in with his tools through the small incision. The doctor says over to me, “I am about to grab the lens now” and just like that a small gray lens is slipped from the tiny incision and placed in a metal bin. The doctor grabs a clear artificial lens with his forceps and gently inserts it into the space the old lens left. With a few more rinses and a secured eye bandage, the patient is sent out of the OR.

Urology

I sit in the clinic alongside the urologist with the GMR team. Our patient walks in and sits in the chair across from the doctor. The patient begins by explaining that recently he has noticed blood in his urine. He elaborates saying that he is experiencing difficulty and pain during urination, accompanied by suprapubic pain. When asked further about his social history, it is noted that the patient spends extended time in freshwater. He has a concerned expression brushed on his face. The doctor quietly writes notes as the patient talks. “I am going to do an exam to check for any changes that may be present on your external and internal genitalia”, the doctor explains. The patient nods and they both stand and make their way into the examination room.

Following the exam, the doctor raises concern that the patient could have an infection called schistosomiasis. Schistosomiasis is found in areas throughout Africa, South America, Middle East, Caribbean, etc. It is acquired from contact with freshwater snails that harbor the infectious parasite. The parasite penetrates human skin and is able to migrate throughout the body to cause infection. When the bladder is infected, this can lead to the presentation seen in this young patient. If left untreated, the infection causes chronic irritation and can lead to bladder cancer. The doctor explains this all to the concerned patient and emphasizes the importance of treatment adherence to prevent further complications. He also advises the patient to have imaging done with his primary care physician. The doctor finishes the patient’s note, detailing what they have discussed along with his prescription. The patient grabs the note and makes his way to the pharmacy.